|

travels

in amira

In

Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A Stately pleasure dome decree

With

such lines did Samuel Taylor Coleridge cunningly trip a switch for his

reading public, introducing them to a mythical land of heightened sensitivity

and super-stimuli: a world of exotic sounds, colours and perfumes; a world

they had never been to, but were in some strange way already familiar

with; a world located somewhere.... in the East.

There

is more than a touch of the Orient about Amira, the mythological land

evoked in the exhibition Travels in Amira by artist Karl Grimes.

Like Xanadu, Amira is a fantasy. It is a confection of all that is delightful,

a place where our visual senses are lightly pleasured and our dormant

prejudices gently reaffirmed.

By

and large, the photographs depict Middle-eastern styled interiors, doorways,

shopfronts and architectural features. Colours are bright and assertive,

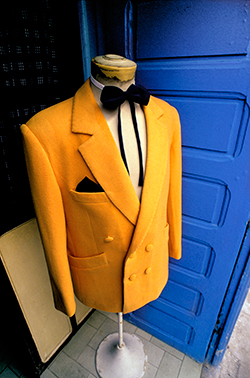

favouring rich 'ethnic' hues. The mundane items depicted - shop dummies,

sift drink bottles, advertising plates - take on the air of exotica that

foreign-ness confers. But here also are familiar Western scenes and icons

- the Empire State Building, the Manhattan skyline by night etched in

neon, plaster busts of Elvis, blonde B-movie starlets. East in West. Or

could it be the other way around? Whichever, all appear to coexist in

Amira.

In

his book Orientalism Edward Said posits the notion that Western

depictions of the East tell us more about our own Western culture than

they can reveal about the 'Orient'. Grimes' exhibition blithely mixing

West and East and vice versa, seems wary of this idea: our perceptions

of one derive from our experience of the other.

Rugs,

wall-hangings, murals and framed portraits occur frequently throughout

these works. They function in a manner of theatrical backdrops, setting

up a series of layered tableaux within the one picture frame, striking

a definitive note of artificiality and illusion. The Oasis of Nefta

depicts a mural painting of desert and palm trees, cruelly punctured by

a roughly gouged wall vent, and teasingly heralded by a real projecting

sprig of greenery. The theatricality is echoed in the installation-like

redecoration that the gallery has undergone. Red walls with golden Arabic

script, white muslin drapery and a tri-faceted text work joyfully ape

a 'middle-easternism'.

The

images are almost filled to bursting point with frames themselves. Window

sashes, picture surrounds, wall ends and rug borders all jostle for position

within the photo frame. In casting the frame as a subject in itself, Grimes

draws attention to its restrictive delineation of the boundaries of a

given perspective. The triptych format employed by each of these pieces

re-stresses the role of the frame in separating individual perspectives,

and in suggesting possible relationships between diverse images. By also

dividing the exhibition space into two areas, Grimes establishes another

level on which this dynamic of separation and relation can be played out.

The

subjects of these photographs are frequently themselves objects of depiction.

Because of close cropping, they tend to fall only partially within the

photo frame, their edges extending beyond the border of the image. What

we see are images of parts of images. Lots of them. The Empire and

the City of Lights shows us not the Empire State Building, but a scaled

architectural model of the same. The Ceremonial Robes of the 12th Court

appear, humorously enough, in a shop window on a tailor's dummy, but

are also present as robes which have been rather crudely painted onto

the shop's window. Photography, the medium of representation par excellence,

seems here to succeed only in capturing the image of existing representations.

Amira

is peopled by a motley collection of personalities, who are present in

so far as their portraits are photographed. The only time we are present

with a live subject, a nude subject, the photographer has called upon

a mirror reflection to capture the image. The mirror is at an angle and

the subject's face and identity are cropped from the resulting reflection.

Despite the guileless nudity, the photographer must rely on imperfect

representational devices to give an account of himself.

The

apparent abundance within these images belies the fact that we are constantly

made aware of what has fallen outside the picture. The photograph's limited

ability to tell the whole story is brought into relief. Urged to suspect

the singular perspective and the integrity of the photo image, we can

draw no comfort from the various captions Grimes uses. The convoluted

titles are as richly evocative and as slippery on meaning as the imagery

they describe.

Madam

Piver is Remembered in the Cafe of the Fondouk, The Court Tailor Displays

the Royal Garments at Sunrise, Queen Ivana Warns of False Gods, all

suggest a sense of history, ritual and fable beyond the superficial acquaintance

with Amiran culture we are offered here. The golden Arabic signs which

decorate the walls look convincing enough, but they remain inscrutable

to the western eye.

Grimes

sets up all these potential meanings in the way of a domino chain, then

gleefully tips them over. It can be exhilarating to watch the chain reaction

as one debunked meaning tips over another and so on. The final triptych

in the sequence of images is entitled The Royal Palmery of Amira.

Of course, the palmery exists only as shadows of palm trees thrown up

against a pink sun-baked wall. Ultimately, this exhibition is an exuberant

celebration of the potency and mastery of such shadows.

Paddy

Johnson

Reproduced by permission from Circa Magazine, Autumn, No 65, 1993.

REVIEWS

Moroney, Mic . 'Fabled zone where kitsch is reality'.

Irish Times, June 18. 1993

Johnson, Paddy. 'Karl

Grimes-Travels in Amira'. Circa, Autumn, No 65, 1993.

|